The master of the Renaissance: Michelangelo is one of that handful of artists whose fame has remained unbroken for centuries. Although his art and ideals are deeply rooted in the thinking of his time – the heyday of the Renaissance and the advancing 16th century – the impact of his art extends to the present day.

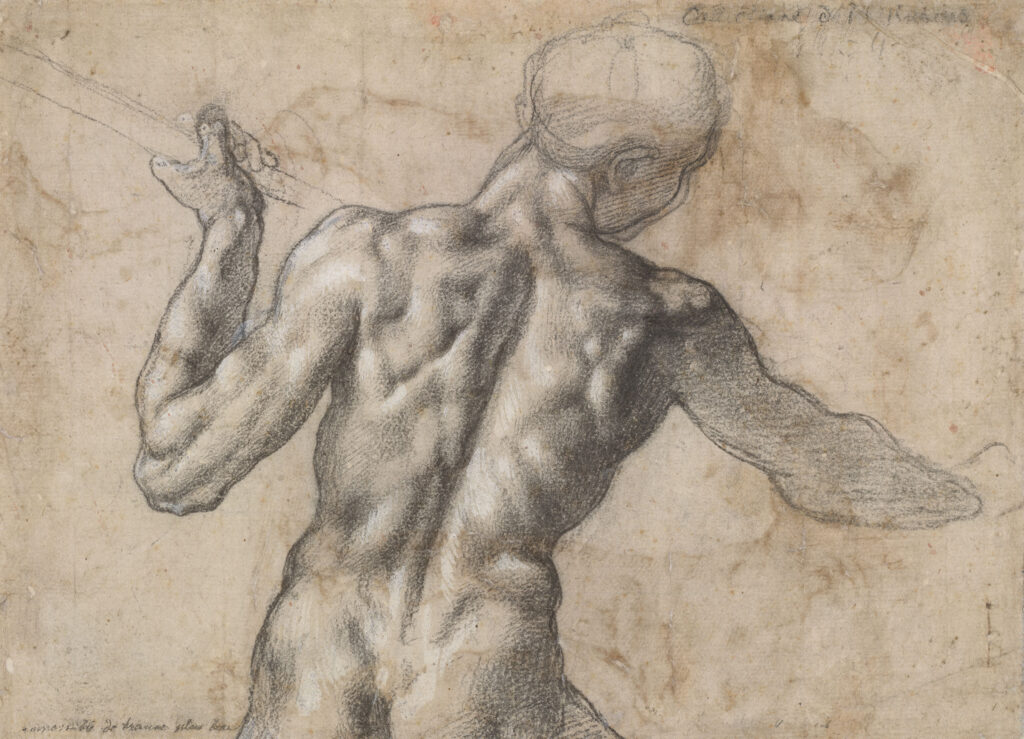

Every century experiences its own Michelangelo Renaissance and with it the revival of that ancient ideal that the great Florentine made an unsurpassed standard for the ideal male nude with his design for the never-executed fresco of the Battle of Cascina, the Ignudi in the Sistine Chapel, and the Dying Slaves for the tomb of Pope Julius II. Michelangelo and the Consequences is about the emergence and power, the decline in significance and the decay of a canon – the canon that Michelangelo left a lasting mark on with his nudes 500 years ago – and about how subsequent generations have worked off this model.

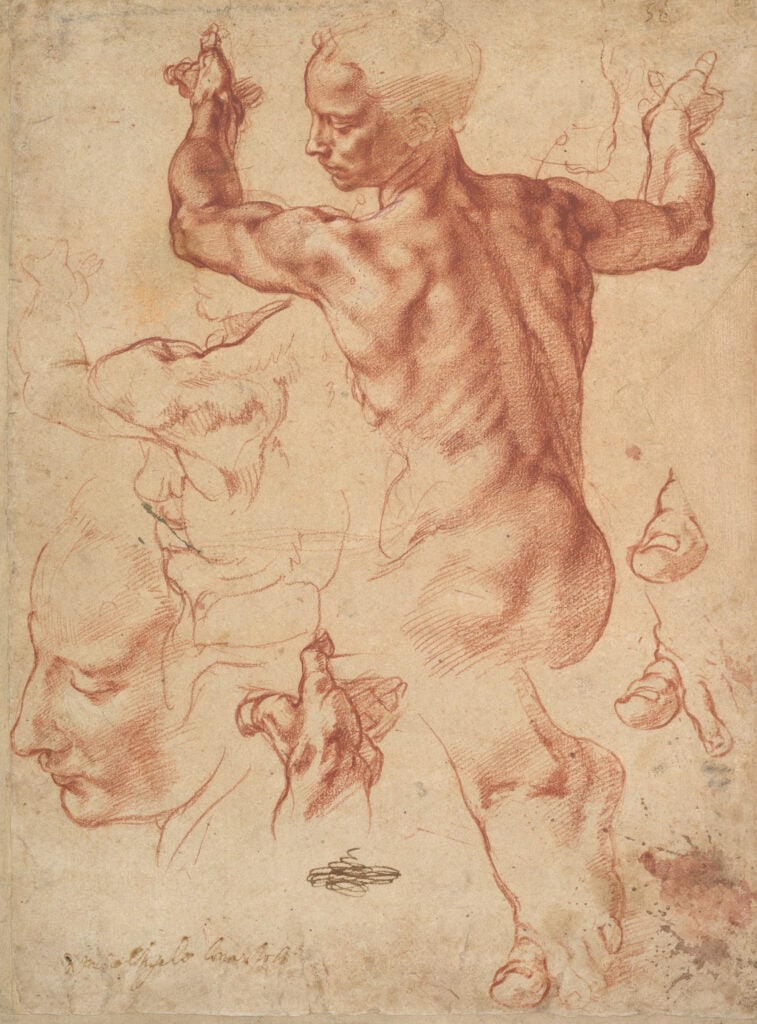

The illustration of the human body

Rötel, weiß gehöht 28 x 19 cm

ALBERTINA, Wien

The rich holdings of the ALBERTINA`S graphic collection allow an examination of Michelangelo’s ideal, which presents itself in an impressive way in his drawings as well as in his sculptures as an athletic and powerful male nude, characterized by inner tensions to the point of tearing.

The new status of the drawing as an independent work of art in the 15th century, which condenses the artistic idea and the temperament of the artist like a condensate, is shown not least by the high demand of collectors for these precious objects. The provenance of the drawings by the Renaissance master in the ALBERTINA shows Peter Paul Rubens as the owner in the 17th century and underlines the importance of the

Italian genius in the following generation of artists.

The classical nude, as it confidently confronts us in the drawings of the ALBERTINA from Michelangelo to Raphael and Beccafumi to Bandinelli, da Volterra, or Salviati, has always sought a harmonious balance between general formulas such as standardized poses, the study of anatomy according to ancient sculptures, or the scaled arrangement of body parts according to Vitruvius’ formalized proportions on the one hand, and drawing according to nature on the other.

Rötel 29 x 21 cm The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1924, inv. no. 24.197.2

Foto: © bpk / The Metropolitan Museum of Art

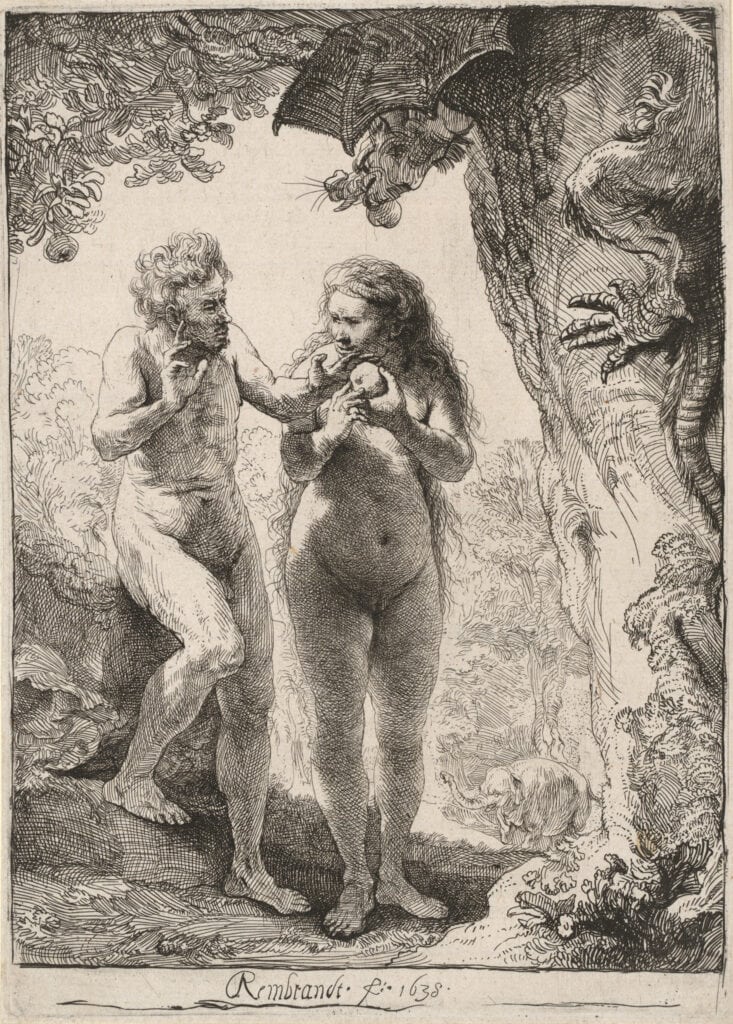

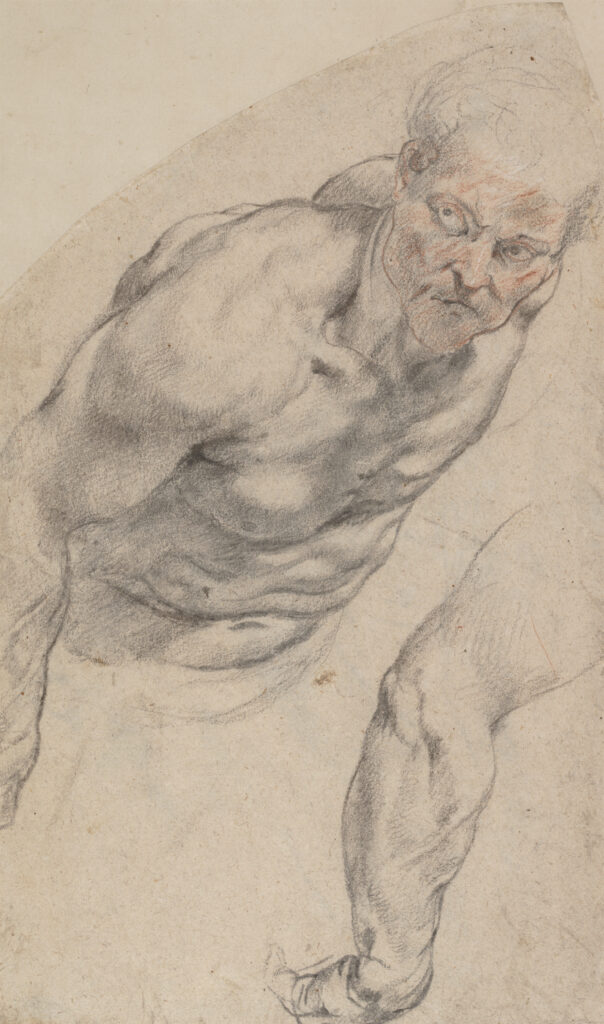

The two artists Rembrandt and Rubens shaped the Baroque with their contrasting positions. Rubens deals with the real, living model and brings ancient nudity to life in a new way. Rembrandt, on the other hand, does not shy away from depicting the ugliness of the real body, of man in his transience and weakness. In doing so, he provides a stark contrast to the athletic bodies of Buonarroti.

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn

Adam and Eva (Der Sündenfall)

1638 Radierung

16 x 12 cm

ALBERTINA, Wien

Peter Paul Rubens

Aktstudie eines Mannes in vorgebeugter Haltung

um 1613Schwarze Kreide und Rötel, mit weißer Kreide

gehöht 40 x 25 cm

ALBERTINA, Wien

In classicism, the type of the beautiful and muscular naked male body, remains. Almost 200 years after the death of the Florentine master, the Michelangelesque canon finds its continuation in the prevailing notion of the ideal nude. Painters of their time, such as Anton Raphael Mengs or Pompeo Girolamo Batoni, create works that trace back to Michelangelo in the precision of the modeling of musculature, the depiction of complicated poses, and the foreshortening of perspective caused by complex postures. They are particularly reminiscent of the masterful drawings that were so important with works such as the Battle of Cascina or the ceiling fresco in the Sistine Chapel.

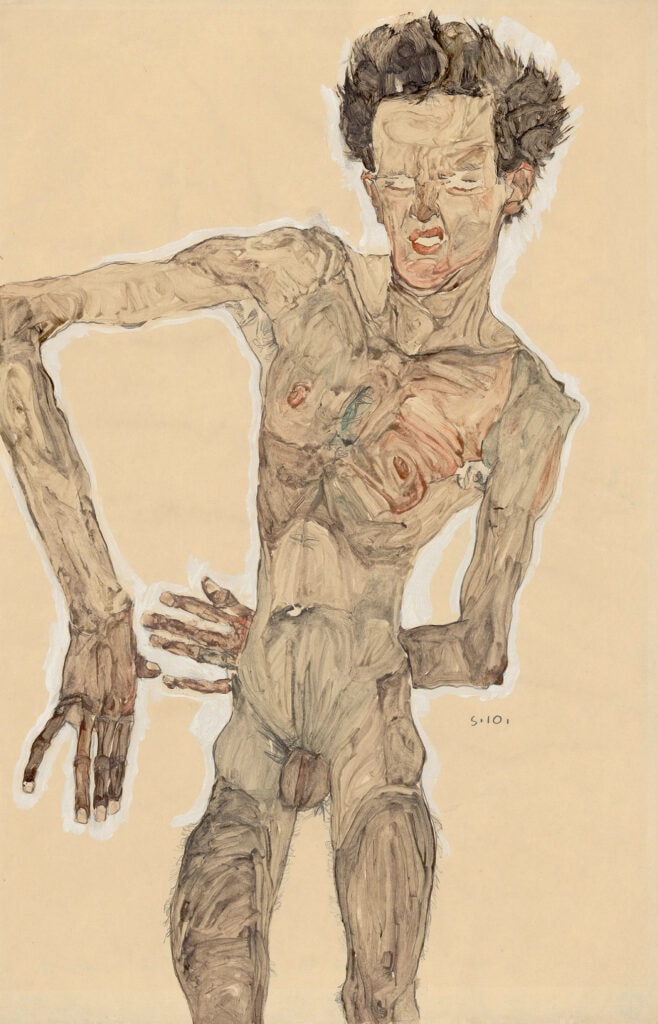

As slavishly as anachronistically, artists still imitate the heroic, athletic figures in the age of Klimt and Schieles: only more externally, on the surface, without the spiritual depth of Buonarroti. The canon coined by Michelangelo has finally passed its zenith, as the representation of the male nude as a symbol of a heroic individual finds less and less resonance in modern society. The show takes its historical cue from the fact that for centuries only men drew men, and women were also depicted only by men. The man defines the canon of the male nude as much as that of the female nude. Michelangelo himself hardly ever draws a naked woman, but lends feminine grace to male bodies.

Gustav Klimt

Studie für die linke der „Drei

Gorgonen“ im Beethovenfries, 1901

Schwarze Kreide

45 × 32 cm

ALBERTINA, Wien

Egon Schiele

Grimassierendes Aktselbstbildnis,

1910

Bleistift, Kohle, Deckfarben

56 x 37 cm

ALBERTINA, Wien

For art, woman is like the back of the moon: One knows that she exists, but she is terra incognita. In a few exemplary examples from the 17th and 18th centuries, the exhibition shows the unrealistic ideal of woman. For a long time the representation of the naked woman is discriminated and defamed by her identification with vice, immorality and sex drive. The immorality of woman brings death and sin in the figure of Eve; the vice of Luxuria appears vain and naked. The Virtues are widely clothed in flowing garments. The counter-image to the virtuous veiled woman describes the naked woman as a woman power, as a witch, as a seductive Venus.

The view at the end of the exhibition is chosen as an example. It is representative of a century in which Michelangelo’s canon has lost its authority and is dedicated to the contrast between the Secessionist cult of beauty on the basis of Gustav Klimt’s curvilinear ideality of woman and the ugliness and pathologization of the nude, deprived of its sexuality for the first time, in Egon Schiele’s work.

Mädchenakt mit verschränkten

Armen, 1910

Schwarze Kreide, Pinsel, Aquarell,

auf braunem Papier

45 x 28 cm

ALBERTINA, Wien

Exhibition dates

Duration: September 15 – January 14, 2024

Exhibition venue: Propter Homines Hall | ALBERTINA

Curators: Klaus Schröder, Achim Gnann, Eva Michel, Martina Pippal, Constanze Malissa

Works: 139

Catalog: German and English (36,90) available in the store of ALBERTINA

Contact: Albertinaplatz 1 | 1010 Vienna |T +43 (0)1 534 83 0 | www.albertina.at

Opening hours: Daily from 10:00 a.m. – 6:00 p.m. | Wednesday and Friday from 10:00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m.

iThere are no comments

Add yours