Ai Weiwei, a renowned a human rights activist, ranks among the most influential artists of our time. This is most comprehensive retrospective of his work to date offering insights into all periods of his career, which by now spans more than four decades, thereby revealing the unique aesthetic principles of his art.

The ALBERTINA MODERN is now presenting his most comprehensive retrospective to date. In Search of Humanity deals in depth with the aspects of humanity and artistic commentary in the work of Ai Weiwei. His earliest works were already characterized by an examination of his native China, where he experienced the effects of the Cultural Revolution as a child through the exile of his father, the great poet Ai Qing. As a young man in New York’s East Village in the 1980s, he witnessed and documented the protest movements there. Back in Beijing, it was the immediate aftermath of the Tiananmen Square massacre to which he responded artistically. His outstretched middle finger, which he held up to well-known buildings as representative objects of power, thus denouncing injustices, ultimately became his trademark. Time and again, the artist addresses power structures and the mechanisms of exercising power, be it the destruction of cultural heritage as an expression of one’s own superiority or the exercise of manipulation, censorship, and surveillance by the state. He unrelentingly takes a closer look wherever he sees freedom of expression and human rights in danger—from the Chinese government’s methods of intimidation and the threats to journalists and political activists to the protests in Hong Kong, the massive restrictions in Wuhan during the outbreak of the corona pandemic, and even his own detainment in 2011.

Klaus Albrecht Schröder, General Director of the ALBERTINA and the ALBERTINA MODERN

Dieter Buchhart, Curator of the exhibition

Elsy Lahner, Curator of the exhibition

On view from 16 March until 4 September 2022.

Header Credit: Courtesy Ai Weiwei | Studio Gao Yuan

Ai regards the current situation of refugees around the world as perhaps the greatest global humanitarian crisis since the Second World War, and as an enormous challenge for us as a solidary society—and he sees each and every one of us as having a responsibility to take action.

Exhibited Works

New York und Peking Photographs

Between 1983 and 1993 Ai Weiwei lived in New York. He documented his impressions and meetings with friends like Allen Ginsberg and Robert Frank using a camera, or he had himself photographed while discovering the city. Casual snapshots served him as a visual diary. Over time, the photographs changed, becoming less private. Through the lens of the camera, he observed events in his immediate neighborhood in the East Village, where Tompkins Square Park became the site of violent confrontations between police and activists and residents in the summer of 1988, when a curfew was imposed to drive away some 200 homeless people who were living in the park. He witnessed the ACT-UP (Aids Coalition to Unleash Power) protests and documented police arrests of demonstrators. The East Village became a stage for political, social, ethical, and sexual concerns, for civil disobedience. Ai joined the activists and, despite violence exercised by the authorities, experienced the possibilities in each individual to change something for the better through their actions. In 1993, Ai Weiwei returned to Beijing to be with his ailing father. Shaped by his time in the United States, he felt like a foreigner in his own country. He walked through the city as an observer and again took his camera along, but he also captured his most personal environment and his dying father.

Coronation

Coronation shows how the Chinese state authorities reacted to the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, from the very first to the very last day of Wuhan’s isolation in early 2020. Within a few days, emergency clinics were installed, 40,000 health workers from all over China were brought to the region, and Wuhan’s citizens were locked into their homes. Using the example of the pandemic, Ai Weiwei offers insights into China’s crisis management and machinery of social control. Through surveillance, ideological brainwashing, and brutal determination, every aspect of society is regulated and monitored. The artist was not in China himself at the time. He therefore hired a crew whose members partly filmed in clandestine. Many of the shots were taken by private individuals who volunteered as participants in the project, so that the events are portrayed from their own personal perspective.

Human Flow

Ai’s commitment and activism with respect to refugees are reflected in many of his works, most notably in Human Flow. For this feature-length documentary, Ai and his film crew shot for over a year in 23 countries and 40 refugee camps, conducting more than 600 interviews. The film seeks to convey the root causes of flight and the conditions under which refugees live: the intolerable circumstances in the camps, where daily routines have established themselves in spite of everything, the hardships of flight, despair, fear, and grief. Ai’s concern is to visualize the scale and impact of this enormous humanitarian crisis.

Early Works

In New York, Ai Weiwei was fascinated by modern and contemporary art, which he saw there for the first time. This encounter resulted in the reorientation of his own artistic practice: he gave up painting in favor of cultic objects and the magic of readymades. However, his objects go beyond what Marcel Duchamp propagated as anti-art with his objets trouvés. In Ai’s objects, psychological, political, and social dimensions push to the fore. The visual joke of a clash of things that have nothing to do with each other is given a deeper meaning that is also rooted in Ai’s biography.

The shovel in brown fur, for example, is evocative of Ai’s father, the writer Ai Qing, who, when in exile, was humiliated as he was forced to clean the communal toilets of the camp. The violin stuck deep in a pair of coarse shoes tied together may similarly make reference to the hard physical labor that intellectuals and artists were subjected to in reeducation camps during the “Cultural Revolution.” Ai’s objects of leather shoes accurately sown together are an expression of his respect for traditional craftsmanship, which also becomes recognizable in many of his later works, where it is opposed to cheap mass products “Made in China.” The concept of these assemblages required the destruction of the original material: clothes hangers were bent, shoes cut apart, shovels deprived of their functionality, axes broken and put together again like a badly healed fracture of a shinbone.

Neolithic Vase with Coca-Cola Logo, 1994

Tongefäß, , Industriefarbe

Privatsammlung

Foto: Albertina, Wien / Lisa Rastl & Reiner Riedler © 2022 Ai Weiwei

Ai held on to this principle after his return to China in 1993. Now, objects of his own culture increasingly shifted into focus, with which he referred to the brute destruction of traditions during the “Cultural Revolution” and the suppression of culture in new modern, capitalist China. The Neolithic vase inscribed “Coca-Cola,” one of consumerism’s most omnipresent logos, is a critique of the culture of forgetting and banishing the old by what is new.

A Metal Door with Bullet Holes

Since 2015, Ai Weiwei has repeatedly addressed the themes of war, flight, and migration in bhis works. He creates readymades from found objects, such as this huge metal gate with bullet holes, which he discovered while filming in Syria near the Turkish border, and which, as one object among many, bears witness to the violence that has recently been so present in this area.

A Metal Door with Bullet Holes, 2015

Metall

Courtesy of the artist

Foto: Courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio © 2022 Ai Weiwei

Mao

Inspired by Andy Warhol’s well-known Mao series, Ai also painted several portraits of Mao Zedong, but as a Chinese citizen of course had different associations. Ai made reference to Mao as a once omnipresent model to try out various painting styles. For these portraits, he resorted to historical propaganda posters from the 1960s, the time of the Cultural Revolution. The horizontal stripes simulate the impression of cheap corrugated iron sheet as a painting ground.

Safe Sex

In 1988, Ai presented his works for the first time in an exhibition entitled Old Shoes, Safe Sex in a gallery in SoHo. The eponymous work Safe Sex, a raincoat with a condom hanging from it at crotch level, can be read as the artist’s response to the major threat of AIDS, which he experienced firsthand in his immediate surroundings in New York in the 1980s.

Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn

Who determines what is precious? Is an object valuable only because it has survived a certain time? Even if it was a mass-produced item at the time when it was made? This Han dynasty urn (206 BC – 220 AD), which the artist smashed to pieces in 1995, prompts us to reflect upon these questions. The subversive action was captured in three black-and-white photographs.

Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995

Schwarz-weiß Fotografien (Triptychon)

Privatsammlung

Foto: Courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio © 2022 Ai Weiwei

Tiananmen Square—At the Gate of Heavenly Peace

Back in China, Ai Weiwei sought to comprehend the protests of 1989 and the Tiananmen massacre on June 4, responding to it artistically. He made it a tradition to visit the scene every year to mark the anniversary of what happened at this historic site at the Gate of Heavenly Peace, the entrance to the Forbidden City, with the portrait of Mao Zedong above it—a place that is also home to his mausoleum.

In 1994, Ai visited the square together with the artist Lu Qing. She stood at some distance in front of the gate so that both the gate and Mao’s portrait were clearly visible in the background, posing as if for a classic tourist snapshot. She lifted her skirt for the photo to be taken by Ai—a seemingly playful, humorous gesture, although only possible for a brief, unnoticed moment in this heavily guarded place, as it amounted to an affront especially at this time. Her pose and the picture thus represent an act protest against the rigid structures of the regime.

Ai’s work Tianan Men is also dedicated to the events that took place on Tiananmen Square, specifically to an incident that would become known as “the egg washing of Mao.” On May 23, 1989, Lu Decheng, Yu Dongyue, and Yu Zhijian, three young men from Hunan who had joined the student movement, hurled ink-filled eggs at Mao’s portrait. The students suspected the three of being spies and provocateurs and turned them over to the police. With this work built of Lego bricks, Ai has reproduced the defacing paint splatters on the image of Mao without showing the portrait itself. As such, the work resembles an abstract painting, and yet it is also an act of protest that has coagulated into a picture and memorial.

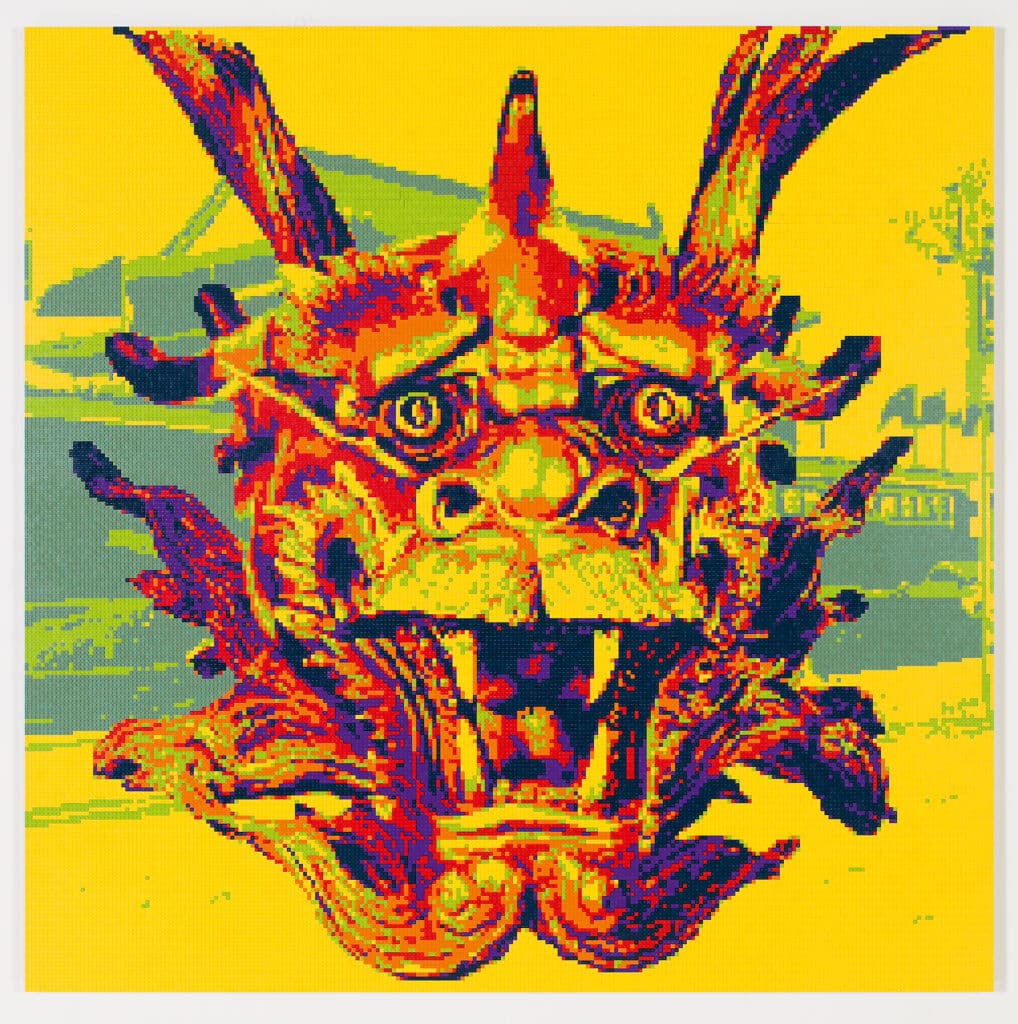

Lego

For several years now, the artist has used Lego bricks as a material—on the one hand because he likes the pixelated appearance of the works and thus refers back to a now-defamiliarized original, and on the other hand because building with Lego has something egalitarian about it.

Zodiac (Dragon), 2019

LEGO-Bausteine

Privatsammlung

Foto: Albertina, Wien / Lisa Rastl & Reiner Riedler © 2022 Ai Weiwei

With the appropriate template, it is possible for anyone to recreate the image, which in turn thematizes the difference between art and mass product. The boundaries between high art and low art are hence called into question.

Study of Perspective

It was again at Tiananmen Square that Ai photographed his extended middle finger for the first time in 1995, directing his protest against those currently in power and thereby taking a stand even more decidedly. Ai later expanded his protest, no longer limiting it to China. Like a tourist, he set his sights on world-famous buildings and works of art, extending his arm into the center of the image with his middle finger raised. His gesture is always directed at symbols and signifiers of political or cultural power, such as the White House in Washington, the Eiffel Tower in Paris, the skyline of Hong Kong, or the Reichstag in Berlin. He has never directed this gest at people, as the artist sees in each and every individual the potential to change things for the better.

Study of Perspective – Eiffel Tower, 1999

Farbfoto

ALBERTINA, Wien – The ESSL Collection

Foto: Mischa Nawrata © 2022 Ai Weiwei

Referring to the title Study of Perspective, Ai employs the art term commonly used for spatial preliminary drawings, thus pointing out that this is a work of art. And instead of estimating the distance with his thumb, as would be the usual thing, he uses his middle finger. On the other hand, the title references his personal point of view and the perspective—or prospect— of changing the future with his action. We see the scenes from the artist’s perspective. Strictly speaking, it could also be our arm that protrudes into the picture. In this way, we are encouraged to question our own position vis-à-vis authorities and to stand up for the rights of autonomy and freedom of expression.

Bicycles

Ai Weiwei created his first bicycle object in 2003. As he had done in his early work, he once again harked back to Marcel Duchamp and his readymades, specifically to Bicycle Wheel (1913), for which Duchamp had mounted a front wheel including the fork to a stool upside down.

Forever Bicycles, 2003

42 Fahrräder

Privatsammlung

Foto: ALBERTINA, Wien / Lisa Rastl & Reiner Riedler © 2022 Ai Weiwei

The bicycle has a specific meaning in China, a country that has long been considered a nation of bicycles. As a child, Ai himself experienced how important it was to own a bicycle to be able to move from A to B. As recently as in the late 1980s, there were hardly any motorized private vehicles in China, and bicycles dominated urban traffic. This changed over the decades, as cities grew and distances could no longer be covered by bicycle. More and more people were able to afford a car and switched modes of transportation, which contributed to the heavy smog pollution in Chinese metropolises. Ai combines all these aspects in his bicycle works. He generally uses a particular model from the Shanghai-based brand Forever. Ai assembles the bicycles in such a way that they are no longer functional: without handlebars, pedals, and chains, and at times even without a saddle. He thus alludes to the Chinese population, to their synchronization and uniformity, their orchestration as a collective, which hardly allows the individual any freedom of movement.

Rem(a)inders

For Rem(a)inders, a play on words with “remainders” and “reminders,” the artist has cut entire bicycles into five-centimeter fragments. As also holds true for many other works, Ai does not see this as an act of destruction. Rather, the object is transformed into another state in which the old is preserved and which recalls it and ascribes new meaning to it.

Cultural Heritage

During his first years back in Beijing, Ai Weiwei regularly visited flea and antique markets. Due to the great construction boom in China in the 1990s, ancient artifacts were frequently found in the dug-up layers of earth and subsequently offered for sale, most of them for relatively low prices. Ai began collecting these objects. Just as he had previously declared found objects in New York readymades or converted them into artistic works in the tradition of Marcel Duchamp, he now once again drew on cultural objects in order to create works of art —cultural readymades. By altering the original objects—by recombining, painting over, or even destroying them—Ai questions their meaning and the value assigned or denied to an object. He also uses these objects to point out how cultural assets from previous eras are generally dealt with during political upheavals, how new rulers have them removed or brutally destroyed in order to lend weight to their own influence and strength. Ai not least refers to the atrocities of the Chinese “Cultural Revolution” (1966–1976), during which millions of people were killed, tortured, or— like his father—banished under the pretext of purification and proletarian renewal. To build a new society, the necessary destruction of the sìjiù (“Four Olds”) was called for: old customs, old habits, old cultures, and old ways of thinking. The result was the destruction of art treasures and books and many historical sites were reduced to rubble.

Tea Brick

Pu’er or pu-erh is a fermented tea produced in the southwestern Chinese province of Yunnan. In a process known since the tenth century, the tea leaves are wilted, steamed, and then pressed into bricks, balls, or patties. This way they can be preserved, easily shipped, and thus exported while they continue to ripen for years or even decades. The artist has adopted the familiar cube shape and created a work of art that echoes the minimalist works of Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Richard Serra, and Robert Morris. At the same time, Ai alludes to the century-old traditions of his homeland, to China as an exporting country, and to its outstanding role as a global economic power.

Feet (Buddha) (Ai Weiwei quote)

“The feet mainly come from the two biggest locations for Buddhist sculpture in the history of China: Quyang in Hebei province and Qingzhou in Shandong province. Most of the objects date from the Northern Wei or Northern Qui dynasties around 1500 years ago. After a revolution or a change of dynasty, such objects would often be destroyed. Here, the destruction happened shortly after the sculptures had been crafted. These fragments of cultural products are evidence of political power. The construction and destruction of religious images or art has been a traditional means of control over people’s minds and aesthetics.”

Feet (Buddha), 2003

Stein, Holzsockel, Holztisch

Privatsammlung, Foto: ALBERTINA, Wien / Lisa Rastl & Reiner Riedler © 2022 Ai Weiwei

Tang Dynasty Courtesan in Bottle (Ai Weiwei quote)

“Within this traditional repository of peripatetic desire and fantasy materializes an elegantly poised stone courtesan over one thousand years old. This work humorously combines symbols of two of man’s chief intoxications while playing off the opposites of unique artifact and disposable object, painstaking craftwork and mass production, antiquity and modernity.”

Souvenir from Beijing

In the course of the modernization of cities, many hutongs, traditionally built Chinese neighborhoods, were demolished to make way for new buildings. These bricks come from such a torn-down hutong. They have been placed in small boxes, which for their part are made of the wood from temples dating back to the Qing dynasty (1644–1911/12). In a way, Ai Weiwei thus pays his last respects to these remains, as one would honor the dead in their coffins. Through the artist’s transformation, the ancient objects undergo reevaluation and redefinition—a process of renewal.

Dust to Dust / Staub zu Staub

The glass jars contain dust coming from Neolithic ceramics the artist broke and ground to the finest particles. The containers put up on a shelf in rows and the title of the work are suggestive of urns holding human remains, of a memorial site. Ai points out that even the most precious earthenware object is made of dust—as are we, who will again turn to dust at some point. Ai also makes reference once again to Marcel Duchamp’s conceptual work, specifically to Air de Paris (1919). It consists of an empty glass vessel and raises the question of what exactly it contains. Similarly, Dust to Dust is about what the dust in the glass jars is actually made of and what value we assign to it.

Sunflower Seeds

Every single one of these sunflower seeds is truthfully and painstakingly reproduced in porcelain by 1,600 artisans in an elaborate, multistage process. Each is individually shaped and painted. Ai Weiwei juxtaposes traditional handcrafted products with “Made in China” goods mass-produced for worldwide export. During the “Cultural Revolution,” Mao Zedong was likened to the sun, and the people to sunflowers turning toward him. The artist thus subverts this visual language that was popular in his childhood. With Sunflower Seeds, he criticizes conformism in China, a state in which the population is regarded as a uniform mass and the individual has no role to play. Instead, he emphasizes the potential of each and every individual to grow—to grow out of themselves. In China, sunflower seeds are also a popular snack, which Ai appreciated during his childhood in exile, when food was scarce. However, a memory that is also burned into his mind is how sunflower seeds were nibbled during camp gatherings in the evenings, when his father was being criticized onstage and humiliated by the audience.

After Van Gogh

In October 2019, a plague of locusts began ravaging East Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and the Indian subcontinent, causing severe crop losses in countries already affected by hardship and poverty. Scientists have established a link between the plague and global climate change, since the unusually heavy rainfall that provides good breeding conditions for the desert locusts is caused by the higher water temperature of the Indian Ocean. Pictures from the affected region reminded Ai Weiwei of Vincent van Gogh’s oil painting Le Semeur au soleil couchant (Sower at Sunset) from 1888. His Lego work could actually be based on both the photographs and the painting. The artist draws a parallel between van Gogh’s field workers and the harsh living conditions in many parts of today’s world.

Map of China (Ai Weiwei quote)

“Map of China is made from the wood of an old temple that was torn down for development. People often ask me if there is a political condition represented here, but it was made according to the material and the possibilities it presented. All joints were made according to each specific shape. The major problem was to resolve how to hold together 100 pieces tightly and precisely. The map is just the shape of it.”

Ai Weiwei

Map of China, 2004

Holz

Privatsammlung

Foto: ALBERTINA, Wien / Lisa Rastl & Reiner Riedler © 2022 Ai Weiwei

Tree (Ai Weiwei quote)

“The trees are dead wood from the mountain ranges in Jiangxi province. Those branches were struck by lightning, or they simply got too old and had been abandoned for decades. So I thought it would be nice to put them back together as one tree, but from a hundred different locations and belonging to different types of trees. We assembled them together to have all the details of a normal tree. At the same time, you’re not comfortable, there’s a strangeness there, an unfamiliarness. And it’s just like trying to imagine what the tree was like.”

Earthquake in Sichuan

In the early afternoon of May 12, 2008, a devastating earthquake of magnitude 7.9 struck southwestern China. Hardest hit was the province of Sichuan, where entire villages disappeared from the face of the earth and towns were completely destroyed. Some 90,000 people died, more than five million buildings were damaged within minutes, nearly six million people were left homeless, and thousands of children were buried under the rubble of their schools.

When Ai Weiwei learned of the disaster, he drove to the region to understand the extent of the tragedy. He researched and conducted interviews on site. It became clear that gross negligence during construction and corruption had led to serious defects that had contributed to the collapse of the school buildings. The matter became a highly controversial political issue just a few weeks before the Summer Olympics in Beijing, which were being promoted with a great deal of propaganda. In his attempt to obtain a list of all the fatalities, Ai encountered massive resistance and thus launched a survey among the local residents on his own initiative. Over the next two years, he and a number of volunteers traveled to 74 communities, gathered information, spoke with bereaved parents, and investigated the condition of 153 schools. In the process, the helpers were frequently intimidated by the police and, in some cases, arrested. Eventually, they identified the name, age, school, and class of the 5,197 pupils who had lost their lives. Incoming data was continuously published on the artist’s blog. The Chinese authorities, having long eyed Ai’s critical blog with suspicion, censored it at first and then blocked it completely. Ai has been deleted from the Chinese Internet as a dissident.

Names of the Student Earthquake Victims Found by the Citizens’ Investigation

Ai is very concerned not to let the events and victims of the Sichuan earthquake fall into oblivion and to keep alive the memory of the circumstances surrounding the catastrophe. By publishing the victims’ personal data and visualizing this alarmingly long list of children who were abruptly torn from life, he makes us aware of every single individual behind the total number of casualties.

Forge

On the campus of Beichuan Middle School, where most of the children had perished, Ai had vast quantities of twisted rebar salvaged and brought to his studio in Beijing—as a visible sign of the school’s inferior construction. With Forge, which can mean both “form” as well as “falsify,” the bent steel bars have become a memorial spread out over a large area on the floor.

Forge (Detail), 2008-2012

Eisen

Privatsammlung

Foto: Albertina, Wien / Lisa Rastl & Reiner Riedler © 2022 Ai Weiwei

Little Girl’s Cheeks

As part of Ai’s survey among local residents, the film lets those affected by the earthquake have their say: teachers reporting on construction defects in school buildings, children having witnessed the horrible disaster. Parents who tried to find out more about the deaths of their children tell that not only was relevant information withheld from them, but that they were also detained by the police and forced to confirm with their signature that they would waive any right to object.

Panda to Panda

For Panda to Panda, Ai Weiwei worked together with Jacob Appelbaum, the journalist and computer security expert who was among those who uncovered that German Chancellor Angela Merkel was being eavesdropped by the American intelligence agency NSA. The work consists of twenty toy pandas stuffed with shredded copies as well as a backup on a Micro SD memory card of the secret documents leaked by whistleblower Edward Snowden. Ai and Appelbaum photographed and filmed themselves throughout the process of shredding the

files and stuffing the animals. In addition, they had Laura Poitras record the events, which resulted in her short film The Art of Dissent. The idea was to send the pandas as data backups to as many different locations as possible. Museums turned out to be particularly safe places, where the data content would be preserved along with the artwork. Subsequently, copies were distributed to activists around the world, including Julian Assange and Edward Snowden himself.

The title Panda to Panda also makes reference to peer-to-peer (P2P) networks, a form of decentralized and egalitarian communication. In China, however, “panda” is also a term for the state’s secret police. At the time of the project, both Ai and Appelbaum were under state surveillance and restricted in their freedom to travel. After his release from secret detention in 2011, Ai was not allowed to leave China. An early supporter of WikiLeaks, Appelbaum had been subjected to repeated police interrogations since 2010; his cell phone and computer had been confiscated or tampered with. With their joint project, carried out under complete surveillance while at the same time remaining transparent, they disclose data and make us aware that the doings of those in power are also under observation.

After Rubens

This work is a Lego reproduction of the famous painting The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus (1618) by Peter Paul Rubens. Ai has replaced the putto near the left margin by a panda, who now follows the events as an unnoticed onlooker. That the artist harks back to famous works, icons of Western art history, can be seen in several of his most recent Lego works. Modifying them slightly, he adapts them to current topics in the world.

Assange’s Treadmill

For Ai Weiwei, investigative journalism fulfills an important role within civil society. He has therefore always been a supporter of Julian Assange, the founder of the disclosure platform WikiLeaks, whose goal is to make classified documents available to the general public. In 2012, Assange was granted asylum by Ecuador and he spent the following seven years as a political refugee in the Ecuadorian embassy in London. Ai visited Assange there for an interview in the summer of 2016. In October, Assange sent Ai his treadmill as a gift, which Ai subsequently declared a work of art in the sense of a readymade.

Assange‘s Treadmill, 2017

Metall, Plastik und Gummi

Privatsammlung

Foto: Courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio © 2022 Ai Weiwei

Those of us who have never experienced being held in a confined place for an undetermined period of time can only begin to imagine this condition. Ai and Assange share this drastic experience. As a kind of electric hamster wheel on which one never moves from the spot, the treadmill visualizes the everyday monotony and hopelessness of such a situation.

I Can’t Breathe

In October 2018, the Saudi Arabian journalist Jamal Khashoggi arrived at his consulate in Istanbul to collect the documents for his marriage. He would not leave the place alive. Audio recordings reveal how Kashoggi, a critic of the Saudi crown prince who lived in exile in the United States, was tortured and then murdered. His last words were “I can’t breathe”—words also uttered by Eric Garner in 2014 and by George Floyd in 2020 among many others when they were killed by US police officers, and which would become the slogan of the Black Lives Matter movement. By inscribing these words in Arabic characters on the Saudi Arabian flag in a Lego work from 2019, Ai Weiwei has transformed it into a banner propagating the right to free expression. He thus explicitly turns against regimes who literally suffocate their critics.

The Cover Page of The Mueller Report

On March 22, 2019, special counsel and former FBI director Robert Mueller presented the findings and conclusions of his investigations to the US Department of Justice. The Mueller Report, as the document is commonly referred to, deals with Russian efforts to manipulate the 2016 US presidential election, from which Donald Trump emerged victorious. The report, published shortly afterwards in redacted form, concludes that while there had indeed been attempts by Russian state protagonists to influence the election results, there was no evidence of cooperation on Trump’s part. The document leaves open whether Trump obstructed investigations by the judiciary in this context, citing circumstantial evidence both for and against this hypothesis. Trump, who in the run-up to the investigations had described them as a “witch hunt,” regarded the report as an exoneration of all accusations. That same year, Ai Weiwei realized this work made of Lego bricks, depicting the front page of the report on a scale that is impossible to overlook. With its pixel effect, the work resembles a greatly enlarged and thus blurred digital photograph.

US Mail

The US mailbox too is a commentary on what happened in the most recent US presidential election. In 2020, Trump criticized mail-in voting, declaring that it would lead to electoral fraud. He also admitted to having deliberately withheld necessary funds from the US Postal Service, thereby torpedoing the timely delivery of absentee ballots. After it had become apparent that he would lose the election, he called it a “big lie,” a stolen election. As a result, many Republican voters still feel cheated out of the election to this day. However, there was and is no evidence of actual election fraud. Ai understands the mailbox as a statement—for free elections and for democratic rights.

Snake Ceiling

While in Sichuan after the earthquake, Ai was horrified to discover the many schoolbags that had turned up among the rubble of the collapsed school buildings. They gave rise to this ceiling sculpture, for which the artist joined some 1,000 black-and-white backpacks with neon-green straps in such a way that a patterned snake emerged, forming the menacing beast, several meters long, above our heads.

First Detainment

In August 2009, Ai Weiwei traveled to Chengdu to testify in favor of Tan Zuoren at a court hearing. The activist had been researching into the construction defects of schools that had collapsed during the massive Sichuan earthquake in 2008 and as a consequence was charged with “inciting subversion of state power.” He was ultimately sentenced to five years in prison. His fellow activists were detained to prevent them from attending the trial as witnesses. Ai and his team were also kept under surveillance and filmed from the moment they arrived in Chengdu.

Then, at 3 o’clock in the morning, police pounded on Ai’s hotel room door. They searched the room and beat him up so brutally that Ai suffered a severe head injury. Subsequently, he was taken into custody. On the way down in the elevator, he managed to take a picture of the mirror image of the scene with his cell phone and post it without being noticed. The selfie, which went viral on social media, shows the two police officers behind him, as well as his friend, the musician and artist Zuoxiao Zuzshou. The photograph, which Ai later also realized as a Lego work, highlights the increasing importance of smartphones and social media in activism. This was an illuminating moment for Ai when the artist became a persecuted critic of the regime.

Disturbing the Peace

In the court case against human rights activist Tan Zuoren, witnesses were detained by the police, including Ai himself. The film documents the events and how Ai confronted the police and authorities to obtain information about the witnesses’ whereabouts and about the incidents in general.

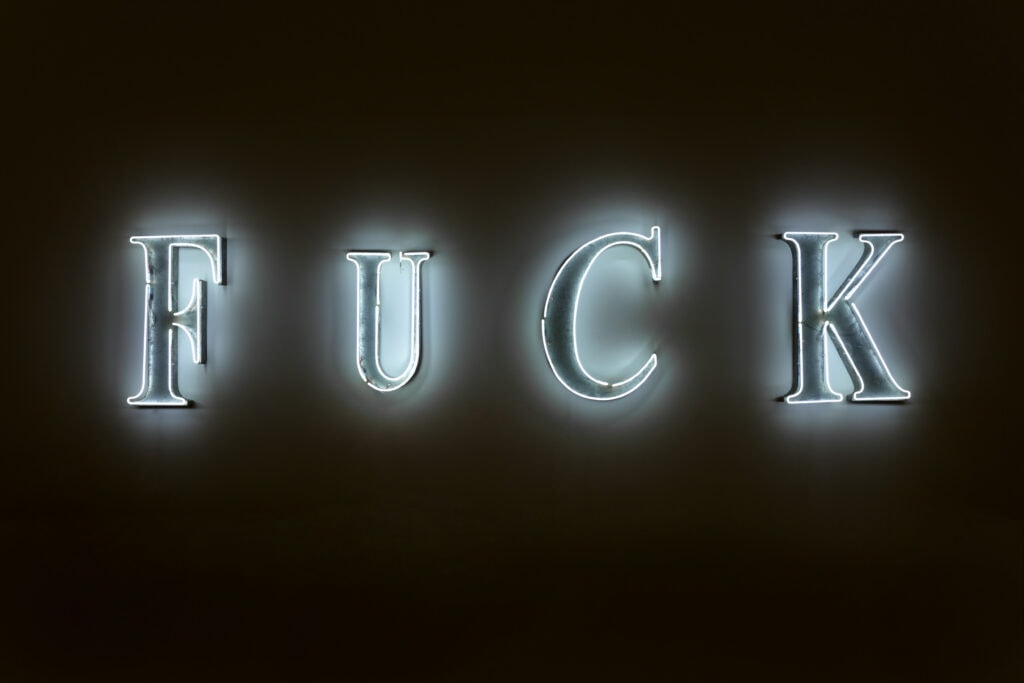

The Animal that Looks like a Llama but Is Really an Alpaca

In Mandarin, the phrase “cào nǐ mā,” literally meaning “Fuck your mother,” resembles the word “Cǎonímǎ.” It denominates the grass mud horse, a subspecies of the alpaca. On the Internet, it is used frequently to avoid possible censorship. This has led to the alpaca becoming an iconic symbol of the fight for the freedom of expression. In his gold-colored wallpaper, Ai Weiwei combines the alpaca with Twitter’s bird logo, handcuffs, and surveillance cameras.

Imprisonment

On April 3, 2011, Ai Weiwei was arrested at Beijing International Airport by the Chinese secret police and imprisoned. For 81 days he did not know where he was, why he was being held, how long his confinement would last, and whether he would ever see his family again. Several times a day, he was handcuffed to a chair and interrogated. Two uniformed guards stood next to him continuously at a distance of eighty centimeters and monitored him around the clock, without speaking and without any facial movement. In the sparsely equipped cell, all furnishings—table, chair, sink, and toilet— were wrapped in polyethylene foam; even the walls were covered with it. The light in the room was never turned off. After Ai’s request to contact his lawyer was repeatedly denied, he finally responded to the standard question of whether he needed anything by asking for a clothes hanger to hang up his hand-washed laundry. The plastic hanger that was consequently granted him was a small achievement, a kind of partial victory. After his detainment, Ai translated the hanger and handcuffs into works of art, using jade, marble and wood.

Handcuffs, 2012

Jade

Private Collection

Photo: The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna / Lisa Rastl & Reiner Riedler © 2022 Ai Weiwei

During those 81 days, Ai memorized the features of the cell down to the smallest detail. He later reconstructed the room on a scale near to life-size as a walk-in installation. Cameras inside the cell transmit the events onto screens mounted outside.

S.A.C.R.E.D.

S.A.C.R.E.D. too refers to the situation of Ai’s secret detainment. Each of the six dioramas presents a scene of his daily routine, with letters being assigned to the respective scenes. Strung together, they form an acronym that functions as the work’s title: S stands for “supper,” showing Ai sitting at the table; A stands for “accusers,” referring to the repeated interrogation; C stands for “cleansing,” showing him taking a shower; R stands for “ritual,” depicting him walking up and down the cell; E stands for “entropy,” meaning a state of sleep; and D stands for “doubt,” showing the artist sitting on the toilet, always under the watchful eyes of his two guards.

S.A.C.R.E.D. (i) S upper, 2013

1 of 6 dioramas in fiberglass and iron

Courtesy of the artist and Lisson Gallery

Photo: Courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio and Lisson Gallery © 2022 Ai Weiwei

In the sense of both “hallowed” and “accursed,” S.A.C.R.E.D. is a reference to homo sacer, a person who, in Roman criminal law, was considered outside the law and could therefore be arbitrarily arrested or killed with impunity. The scenes can be viewed through observation windows placed on top or on the sides of the dioramas, where we ourselves take on the role of those who keep the artist under surveillance, thus invading his privacy. With his dioramas, the artist has found a way to visualize his everyday life in prison in an easily comprehensible form that is reminiscent of a dollhouse while at the same time having the audacity to make the conditions of his imprisonment public in a work of art.

Dumbass

On June 22, 2011, Ai was released from his detainment without formal charges, but placed under house arrest and subjected to continued surveillance; his passport was confiscated. Two years later, together with Zuoxiao Zuzhou, he released the progressive rock video Dumbass, in which he depicts the circumstances of his confinement with quite a bit of selfirony while sharply criticizing China’s policies.

Furniture Sculptures

In his works made of wood, Ai is also concerned with cultural heritage and the handling of cultural assets. For his furniture pieces, he harks back to traditional Chinese furnishings and has them rebuilt by accomplished cabinetmakers according to his ideas. In doing so, he makes a point of using the same historical techniques of craftsmanship that have been used in China’s furniture making for ages, with invisible joints holding the individual parts together and working methods depending on the material. Nothing new is added, and nothing old that is removed is lost.

Grapes, 2011

40 Holzstühle

Privatsammlung

Foto: Albertina, Wien / Lisa Rastl & Reiner Riedler © 2022 Ai Weiwei

Through the new arrangement, the furniture has however lost its functionality. The pieces have become shockingly useless, deprived of their actual purpose. New purpose has been assigned to them as works of art. In its wit, this group of works, consisting of bizarre tables and surreal arrangements of plain stools, builds on Ai’s early New York works, on Dadaism and the pleasure it takes in destruction: a three-legged table hopping into the corner, another table leaning lazily against the wall.

Furniture (Ai Weiwei quote)

“When I began making furniture works, I was collecting antique furniture and had learned quite a lot about it. I didn’t want to make anything new. I wanted to use the old, and use its own logic, because antique Chinese furniture has a very special way of construction. Very clear, very principled about proportion and structure and always made according to the type of wood. There’s no nails, yet even if the table is used for a hundred years, it will never break. It really reflects the Chinese understanding of aesthetics and their relation with nature. So I wanted to reconstruct or to disturb or to destroy the original, but without traces. We took great care with the cutting and sanding to make sure the patina of the furniture looked untouched; even an expert would be confused because everything is so perfect.”

Marble

Whenever Ai Weiwei has sculptures created from marble, his aim is literally to add weight to the objects he recreates so as to transform them into monuments. The marble the artist uses comes from the Taihang Mountains near the Fangshan district in Beijing, where this pure white stone has been quarried for more than a thousand years to build palaces, temples, and monuments. In China, as in Europe, marble is considered a symbol of power, grandeur, permanence, and eternity. That is why this material was also used under communist leadership, as exemplified by Mao Zedong’s mausoleum. By using marble, Ai references these attributions while playing with our perception.

Marble Sofa, 2011

Marmor

Privatsammlung

Foto: ALBERTINA, Wien / Lisa Rastl & Reiner Riedler © 2022 Ai Weiwei

Ai’s Marble Sofa, which looks like a crumpled, slightly worn leather armchair, turns out to be a cold, hard, and therefore rather uncomfortable stone sculpture. The artist alludes to a specific sofa model that could be found in millions of living rooms in the 1970s, and which became a sign of domestic comfort and social status. However, it is also reminiscent of the marble armchair in which Chairman Mao, also carved in stone, is enthroned in the antechamber of his mausoleum.

Marble Doors

The marble doors are based on wooden doors from houses built in the traditional hutong style. They were demolished in the course of urban renewal and continue to be torn down to make way for larger residential units. Doors of this type are therefore to be found in masses on the large garbage dumps of big cities. By recreating them in marble, Ai lends permanence to these discarded pieces of household inventory while questioning China’s radical modernization.

Circle of Animals / Zodiac Heads

The Old Summer Palace near Beijing, known as Yuanmingyuan, was a complex of palaces and gardens that had been designed by Jesuits in European style. Part of it was a water clock in the form of a fountain featuring twelve waterspouts, each of which was shaped like the head of an animal of the Chinese zodiac. In 1860, during the Second Opium War, Anglo-French troops looted and largely destroyed the Old Summer Palace in an act of reprisal, and they also removed the heads of the fountain figures. Several of them have been considered lost ever since, others made their way into private ownership and only turned up at auctions in recent years, where they were sold for millions. Since the Chinese consider the destruction of Yuanmingyuan a trauma, and the sale of the animal heads is felt by many as salt rubbed into the wound, the auctions were accompanied by protests demanding the return of these national treasures. While one head proved to be a forgery, seven of the twelve heads are now held by Chinese museums.

Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads (Gold), 2010

12 bronze statues with gold plating, wooden bases

Private Collection

Photo: The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna / Lisa Rastl & Reiner Riedler © 2022 Ai Weiwei

Ai Weiwei’s gilded bronze heads are reinterpretations of the figures. For him, the zodiac fountain raises a number of questions touching on the treatment of cultural assets, the relations between East and West, and the differentiation between original, copy, and forgery. In his view, the animal heads do not in fact represent national treasures, since they were a case of Europeans catering to Chinese tastes, which is why they embody an early example of global consumption. The artist reconstructed the animal heads according to his own ideas to complete the circle, but also to call the original into question with his copies.

Zodiac

Ai also realized the Chinese zodiac in Lego. The heads correspond to those of his gilded zodiac sculptures, but a specific background has been assigned to each of the twelve animals: namely those monuments to power at which Ai sticks out his middle finger in the Study of Perspective series of photographs. The dog is set against the White House in Washington, while the Eiffel Tower looms behind the pig and the rooster’s crest echoes the Sydney Opera House. Western and Eastern icons mingle. In their garish colors, the Lego pictures are reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s screenprints.

Flight (Ai Weiwei quote)

“Today, more and more people are being forced to leave their ancestral homes, for all kinds of reasons—war, religious discrimination, political persecution, environmental degradation, hunger, poverty. Will we ever be able to eliminate these scourges? Can a civilization that is built on the misfortune of others carry on forever? And who can be sure that they themselves will not be torn from their homes one day and cast onto a foreign shore, only to encounter discrimination and be forced to beg for sympathy?”

The Navigation Route of the Sea-Watch 3

At first glance, this Lego work seems to resemble an abstract painting or drawing. However, it depicts the navigation route of the rescue ship Sea-Watch 3. Under Captain Carola Rackete’s command, it rescued 53 refugees off the Libyan coast in June 2019. Attempting to bring the people to a safe place, the port of Lampedusa, the ship was prevented from entering the harbor by the Italian government for two weeks.

Replicas in Marble and Porcelain

Ai’s marble objects often also have a social or political context, in addition to a personal one. The fragile-looking marble chair, for example, made from a single block of marble, imitates a traditional wooden chair with a yokeback. Ai’s family also owned such a chair. It was one of the few items his father, Ai Qing, was allowed to take with him when he was sent into exile in 1958.

Surveillance Camera with Plinth, 2015

Marmor

Privatsammlung

Foto: Albertina, Wien / Lisa Rastl & Reiner Riedler © 2022 Ai Weiwei

The construction helmet is reminiscent of the helmets worn by aid workers searching for survivors after the disastrous earthquake in Sichuan in 2008. In this case, however, the artist actually refers to a different incident: the collapse of a coal mine in which a worker was buried. Fearing that he would not be found in time, he wrote a request inside the helmet, asking his wife to raise their children alone and pay back a small amount of money he had borrowed.

During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) it was fashionable at the imperial court to reproduce commonplace objects in exquisite materials. Although they did not serve any specific purpose, they did highlight the wealth and prestige of the ruling dynasty. Ai took up this tradition when he reproduced a simple toy car, which an artist colleague had given to his then one-year-old son, thereby placing the gesture of friendship on a pedestal.

A similar motivation holds true for the pair of watermelons. They remind the artist of the time of the family’s exile in the desert of Xinjiang, where he lived with his father in the poorest conditions in an underground hovel. Looking back on these difficult years, one of few happy moments that remains is when they enjoyed this particularly sweet fruit.

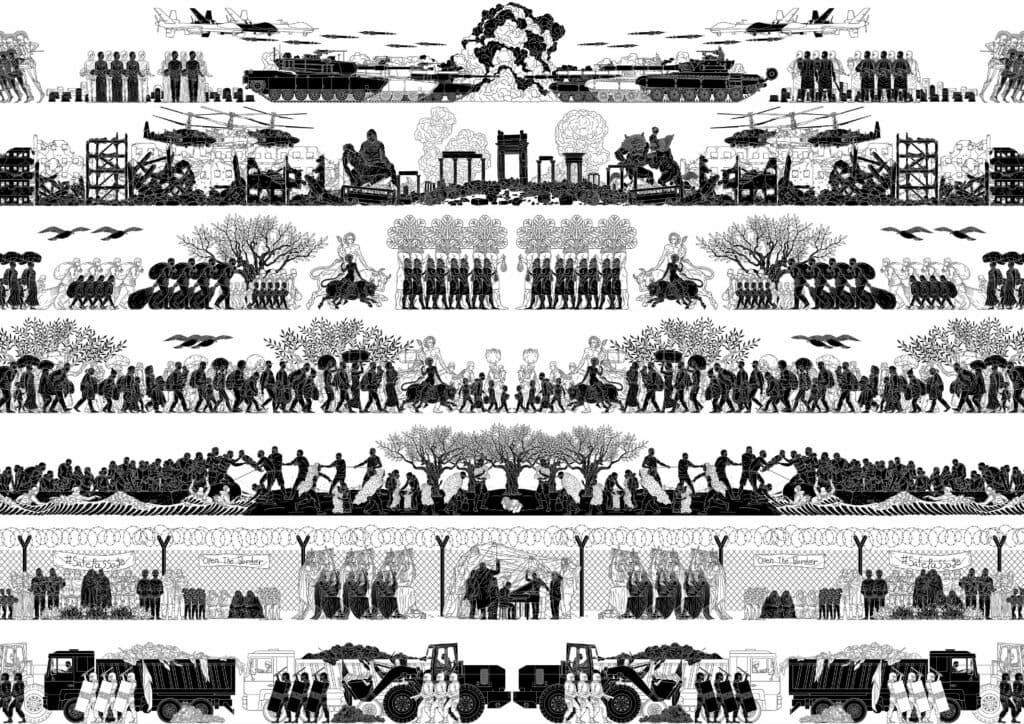

War, Flight, and Migration

In July 2015 the Chinese authorities gave Ai his passport back, and he was allowed to travel again freely. He relocated to Berlin, where he witnessed the effects of the stream of refugees and the associated political discussions in Europe in the fall of that same year. During a vacation on the Greek island of Lesbos in December, he was confronted with the arrival of overcrowded boats with the young, the old, and the infirm, whereupon he went to the Moria refugee camp. He decided to become more involved politically and transferred his studio to Lesbos, beginning to do research and shoot films. Many of Ai’s works were created in the context of his investigations, including this pillar made of porcelain. It shows six motifs dealing with the situation of refugees: war, the ruins of war, flight, crossing the sea, refugee camps, and the demonstrations and protests in the camps. The depictions are reminiscent of ancient Egyptian and Greek pottery, while the blue andwhite decoration harks back to traditional Chinese porcelain. Through these associations, Ai embeds the depicted scenes in a historical context.

Odyssey (Ai Weiwei quote)

“The refugee crisis has a much broader context. There are different histories, regional and religious conflicts, economic pressures, and environmental crises that have contributed to what we understand to be the refugee crisis. My team and I studied this beginning with the earliest human movements, stretching back to the Old Testament. With the wallpaper specifically, we tried to come up with a visual language directly inspired by drawings found in early Greek and Egyptian carvings, pottery, and wall paintings. Within that context, we integrated the new conflicts, with images found in social media and on the Internet, as well as images from my own involvement.”

Odyssey, 2017

Wandtapete

Courtesy of the artist

Foto: Courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio

“Beyond the images, we also examined literature and the political conditions of the various periods. It took more than half a year to finish the drawing, which relates to six themes: war, the ruins resulting from war, the journey undertaken by the refugees, the crossing of the sea, the refugee camps, and the demonstrations and protests.”

Refugee Camp Power Supply

This found object, which Ai Weiwei has declared a work of art, comes from an abandoned makeshift refugee camp in Idomeni. In every camp, where communication means everything, the telephone center is one of the busiest places, with thousands of people trying to get in touch with their families left behind in their homeland, inquiring about the best route to Europe, or recharging their cell phones at charging stations like this one.

Crystal Ball

When Ai stayed in Lesbos in December 2015, he saw the island’s shore covered with life jackets and buoys the refugees had used as they crossed the Mediterranean. Life jackets hence appear in several of the artist’s installations and sculptures on the subject of flight. Here the vests form the blossom of a lotus or water lily, with a crystal ball resting in its center. Perhaps, after war and hardship, after leaving home, the crystal ball affords a glimpse into an uncertain future.

Crystal Ball, 2017

Kristall, Rettungswesten

Courtesy of the artist and neugerriemschneider, Berlin

Foto: Courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio © 2022 Ai Weiwei

Tyre

With this work, the artist sets a monument to those who lost their lives while fleeing across the Mediterranean Sea. In 2021 alone, more than 1,500 people died, most of them by drowning. In 2016, it was more than 5,000. Stacked on top of each other, the marble tyres are intended to commemorate these victims, who risked everything in search of a better life for themselves and their relatives. The chosen material, however, also conveys the emotional coldness with which refugees were, and continue to be met in Europe.

After the Death of Marat

In September 2015, little Aylan Kurdi, a three-year-old boy of Syrian origin, drowned during the crossing to Greece. The picture of his lifeless body on the beach of Bodrum went around the world, newspapers printing it on their title pages. The snapshot bundles the tragedy of a restrictive immigration policy. Ai Weiwei too was touched by the event. Several months later he had himself photographed in the same pose for the magazine “India Today”—which in the eyes of many went too far and caused quite some uproar. Some considered the recreation of the photograph as ethically unacceptable while others accused the artist of exploiting the boy’s fate for his publicity. Ai emphasized that it had solely been his intention to raise awareness again of the misery of refugees with the picture and that he wished to counteract forgetting, forgetting through habituation. Aylan’s father later thanked Ai for this monument to his son and his death in a personal letter. Moreover, the posture adopted by Ai also corresponds to the one Ai was forced to take when he was detained in 2011 and which the Chinese artist He Xiangyu immortalized that same year as a lifelike sculpture entitled The Death of Marat. With this Lego work called After the Death of Marat, showing the picture of Ai on the beach, Ai makes reference to the sculpture and his own pose.

Floating

Ai filmed the three video segments with his iPhone in Lesbos. The sequence “At Sea” shows people in boats trying to cross the sea to Europe. In “Floating,” we see an abandoned rubber dinghy that Ai discovered floating in the middle of the sea and which he boards and inspects in “On the Boat.”

Exhibition Facts

Duration:: 16 March until 4 September 2022

Venue: ALBERTINA MODERN, Ground floor

Curators: Dieter Buchhart, Elsy Lahner

Works: 144 Objects

Opening Hours: Daily 10 am – 6 pm