Column by Helder Suffenplan: The flowery perfume descriptions from some brands make it sound as though every spritz will take us one step closer to Mother Nature:

The creation “is inspired by the intoxicating smell of a tuberose field at night” (Matière Première), “captures the feeling of a summer’s day” (Penhaligon’s) and “tells the story of a fragrance dotted with flowers, water, trees, and rocks (Hermès). And fragrances can actually convey a sense of being close to nature, even in the midst our urban everyday lives: with nature on our skin and in our noses, we become part of nature. But what does Mother Nature have to say about it?

Essences and extracts from flowers, leaves and roots, dissolved in pure alcohol – where’s the problem in that? Every Eau de Toilette is an extremely complex product, whose production touches on many aspects that are relevant to sustainability: water and land consumption, overuse of land, CO2 emissions caused by transport and manufacturing, the use of fossil-based resources, generating waste, and much more.

The annoying thing is that it’s not always clear which solution is sustainable and which is harmful to the environment, so which is the good one and which is bad. Doing or buying the right thing is sometimes not that simple and you can quickly get lost in the details. But don’t panic! In this article, we’ve got a couple of recommendations that are guaranteed sustainable.

Let’s start with the main component of the 1,200 new perfumes that are launched every year: ethanol. When manufacturing using fossil-based raw materials, the carbon footprint is considerably larger than if you were to use biomass. If you consider the area of land required for the cultivation of corn or grain, the matter is suddenly more complicated: complete biosystems and biodiversity affect the climate. And in fields where biomass for ethanol is cultivated, no food can be grown. Coty (Boss, Gucci, Calvin Klein and other fragrance licenses) is already using small amounts of carbon-negative alcohol, during the production of which carbon dioxide is removed from the atmosphere. Other manufacturers want to follow in their footsteps. Recently, there have also been water-based perfumes that avoid alcohol altogether, for example from Behnaz Sarafpour and Buly 1803 (my recommendation for summer is Eau Triple Kiso Yuzu).

Now for the ingredients that make a fragrance a fragrance: the aromatic substances. “All natural”, “100% natural ingredients” – it sounds good, like everything has been done right. Apart from the fact that the perfumers are creatively extremely restricted if they’re only able to use natural aromatic substances, so it’s worth looking a little closer. Naturals aren’t harmful to people or the environment, per se, but many have been linked with the development of allergies or even cancer, so they’re being increasingly regulated. The predominantly agricultural production method uses inordinate volumes of water and areas of land: if all the products in the world that smell like roses actually contained real rose, every piece of land on the planet would have to be planted with the queen of flowers (as some very clever brain has worked out). There are often dozens of ingredients in a fragrance and they have to be gathered from every corner of the globe: vanilla from Madagascar, vetiver from Haiti, mint from the USA. They are almost always transported by container ships that run on oil. Synthetic molecules would appear to be a much better solution.

Synthetic molecules require less water, no land and are generally less harmful. But manufacturing them demands a huge amount of energy and emits CO2. The world’s largest chemicals company BASF uses the same amount of electricity in a year as the whole of Denmark and generates some of it in its own gas-fired power stations. In the wake of the electrification of its production processes, the company’s electricity requirements could triple by 2035. We’re also talking about petrochemicals here: crude oil and gas form the basis of virtually the entire modern chemical industry.

The major fragrance manufacturers who create and produce perfumes for most of the big brands are now going to great lengths to make their production processes sustainable and have set themselves ambitious climate goals. DSM-Firmenich, for example, promises to be climate-neutral by 2025 and even climate positive by 2030, meaning it will remove more CO2 from the atmosphere than it emits. The goal is also to generate no waste during production, and instead to find a use for all by-products, for example using the huge amounts of water used in the extraction of floral essences as floral water in cosmetics. Bad harvests and shortages of raw materials have long since made these companies aware of their dependence on natural essentials and the vulnerability caused by extreme weather, hence their pioneering role in this regard.

When it comes to sustainability aspects, you can see that perfume is a product that reflects nearly all the existential challenges of our time. And so far, we’ve only discussed the “juice”, as in the liquid in the bottle.

But what about everything else around it, the bottle and the packaging? You can’t see a fragrance and the actual product is mostly just a colourless liquid. This is where the container, the packaging and advertising come into play – to let your eyes do the smelling. The distinctive bottle, the feel of the lid, the outer packaging, everything conveys what we can expect from the scent itself.

Here’s the good news: even though it is often unclear from the ingredients which is the most sustainable path, when it comes to packaging things are a lot more straightforward. The less packaging there is, the more often and the longer it is used for, the better. The ideal situation would be a glass bottle without any outer packaging that can be continually refilled, then at the end of its life span, can be separated into glass, metal and plastic for recycling.

The reality today is sadly rather different in most cases: the production of glass is very energy intensive. The various materials (lid, spray nozzle with tube) are generally impossible to separate from one another. After use, the part strays into the general household waste, as do the oversized cardboard packaging (printed, lacquered, foiled), the foam inlays and the cellophane wrapping.

But things are moving in the right direction: the market share of refillable perfume bottles in Europe increased to 6% in 2022 (NPD market research). Almost all premium brands are now offering individual refills, be it Prada, Mugler or Chloé. At Kilian Paris, all bottles can even be refilled as many times as you like, including the incredible rose-scented fragrance Roses On Ice. LVMH (which comprises Dior, Kenzo and Guerlain, among others) wants to use bioplastics for the caps in future.

The pioneers are often the small niche brands, like Ffern in London with its 100% recyclable outer packaging made out of paper and compostable mycelium, and kraft paper tube instead of a cap. The bottles from label Henry Rose, which was founded by Michelle Pfeiffer, consist of 90% recycled glass and the caps are made out of soy. I particularly like Torn from this brand, created by perfumer Pascal Gaurin. The question for the future is whether outer packaging is necessary at all if the bottles are designed to be so smart and iconic.

The fact that many perfume store shelves look like a cabinet of sustainability horrors demonstrates that there’s still a long way to go. Some brands are creating a real battle for themselves with creations that remind us of budget toy shops: bottles in the shape of stilettos and lightning bolts (Carolina Herrera), trophies and robots (Paco Rabanne) and handbags (Marc Jacobs). They’re all made out of a mix of glass, plastic and rubber, rhinestones and mica, and Moncler has even incorporated an LED strip. How long does it take for these materials to decompose in the environment? Several thousand years.

In addition to enhanced environmental awareness, there is obviously a need to redefine our idea of luxury. A little tweak here and there won’t be enough to safeguard our future on this planet. What it requires is less of everything in favour of something better and more intelligent. Moving away from the kind of luxury that’s characterised by waste towards a luxury that focuses on quality and a clean conscience. The joy found in fragrances wouldn’t disappear if it weren’t concealed under layers of packaging and kitsch. Perhaps then we would even concentrate more on the act of smelling itself.

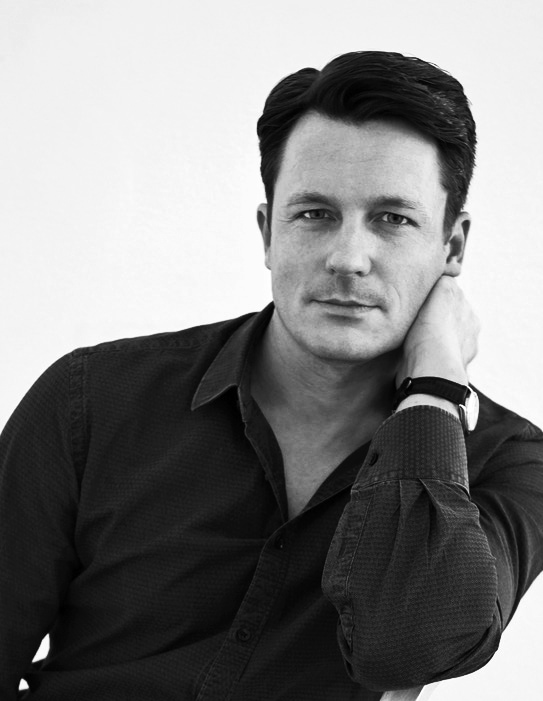

HELDER SUFFENPLAN

is an independent publicist and creative consultant from Berlin. He has had a special passion for perfumes since childhood. With the successful launch of SCENTURY.com – the first online magazine for perfume storytelling – in 2013, Helder became a recognized figure in the global world of fragrance. He has been a jury member for The Art & Olfaction in Los Angeles or the Prix International du Parfumeur- Créateur, Paris, among others. As an author, he combines his favorite subject of perfume with diverse fields such as contemporary art, pop culture, literature, film and geopolitics.

Photo: Holger Homann