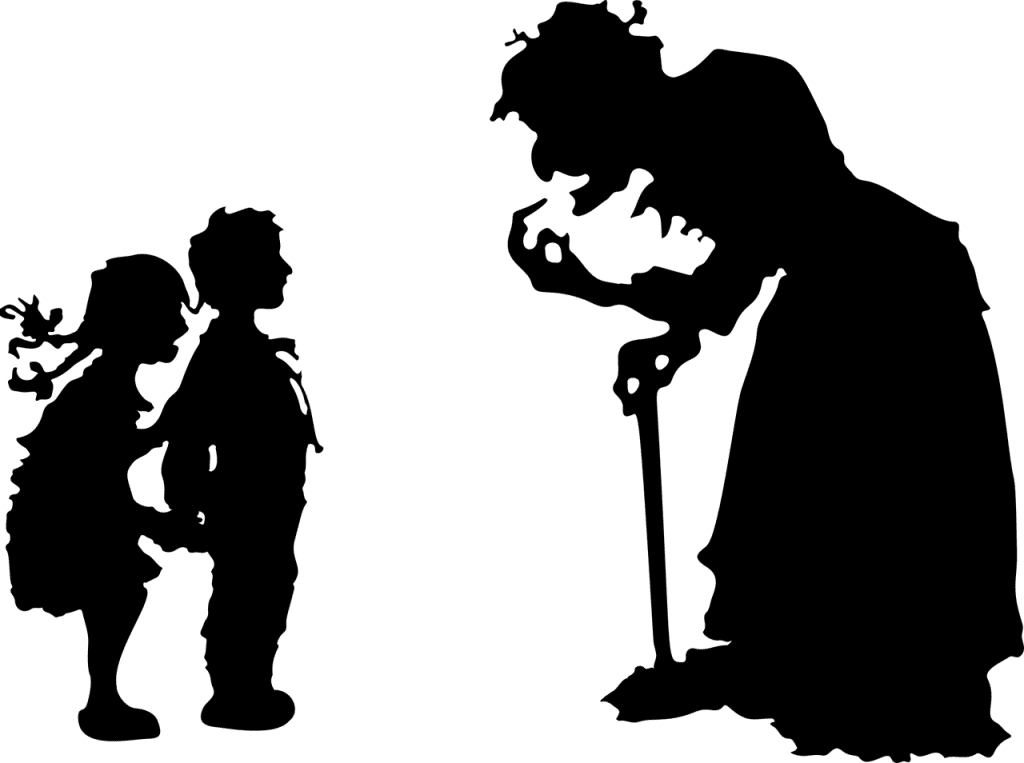

Hansel and Gretel reloaded

Perfection is fleeting, so we need to see the beauty in the imperfect – that’s how the Japanese live with their philosophy of wabi-sabi, according to which all things are charming, even those with flaws. But it hasn’t been possible to carry this idea over to people, because in the land of the rising sun, it’s still business as usual: pressure, perfectionism, success.

The world has seen many political woes

Class struggles, racism, the fight for equality. Fifty years ago, demonstrators were shot at in Western Europe, resulting in violence and retaliation. First came the student riots, then there was the German Red Army Faction (RAF), who burnt down department stores, carried out kidnappings and committed murders. Hansel and Gretel were in the thick of it. Both groups came from homes with authoritarian parents and saw the state as an extension of their tyrannical, abusive fathers. Both groups fell in with the RAF, wanting to show those in power that they were no longer safe, leading to attacks, prisoner liberations and escape. Hansel and Gretel were young and believed they were invincible. They may not have actually been violent themselves, but they were prepared to be, so they were arrested, they sat in prison and they survived.

Today, the former troublemakers of the middle class live in a modest little house on the edge of the forest and receive a small pension for the jobs they did after being released from incarceration. Every morning, Hansel mixes olive oil with oats and spoons the porridge onto a plank of wood next to the veranda, and blue tits, nuthatches, starlings and young woodpeckers arrive not long after. The best singer is the blackcap, an unremarkable grey bird for whom the vitex shrub, which is also known as the chaste tree and is alleged to lower libido, was especially planted. Next to it are the gazanias, because they attract the greenfinches, and elder, which is meant to deter moles. The birds have barely had their fill when Harvey the squirrel arrives and collects up the nuts that Hansel always has in his pocket. Harvey quite literally eats out of the palm of his hand. Then there’s Susi, the mother fox who has to support her young in two burrows – she looks understandably emaciated, but Hansel and Gretel don’t feed her, as you’re not supposed to feed predators. Frogs live in the pond and racoons come to visit at night.

Books about songbirds and garden plants are piled up on the dining table. Whereas before Hansel and Gretel read Marx and Mao and ranted about the demon that is capitalism, they now take great interest in flora and fauna and are happy. They have found nature, and in doing so have found themselves.

People are happy when life is affordable, when it has flavour and they’re able to enjoy it.

This last part in particular is lacking for many. Most people think that money makes you happy because it can act as an iron to smooth out all the lumps and bumps. But money only serves to make you unhappy when you don’t have any. There is no such thing as a perfect life, so we have to learn to accept the minor flaws and be more wabi-sabi. There are no definitive truths, but for Hansel and Gretel life now seems to be much more honest. They no longer want to change society, preferring instead to focus on helping Harvey and the birds make it safely through the winter. For them, their life is less about anti-imperialist class struggles and more about species-specific feeding and the phases of the moon – the kind of cottage garden mentality they would have laughed at before, but which now gives them great joy.

Franzobel is an Austrian writer. He has published numerous plays, works of prose and poems. His plays have been produced in countries including Mexico, Argentina, Chile, Denmark, France, Poland, Romania, Ukraine, Italy, Russia and the USA.

His great historical adventure novel “Das Floß der Medusa” (Zsolnay publishing house) was awarded the Bayerischer Buchpreis (Bavarian Book Award) 2017 and was on the shortlist for the German Book Prize 2017.

iThere are no comments

Add yours